Smart Rollups

Smart Rollups play a crucial part in providing high scalability on Tezos. They handle logic in a separate environment that can run transactions at a much higher rate and can use larger amounts of data than the main Tezos network.

The transactions and logic that Smart Rollups run is called layer 2 to differentiate it from the main network, which is called layer 1.

Anyone can run a node based on a Smart Rollup to execute its code and verify that other nodes are running it correctly, just like anyone can run nodes, bakers, and accusers on layer 1. This code, called the kernel, runs in a deterministic manner and according to a given semantics, which guarantees that results are reproducible by any rollup node with the same kernel. The semantics is precisely defined by a reference virtual machine called a proof-generating virtual machine (PVM), able to generate a proof that executing a program in a given context results in a given state. During normal execution, the Smart Rollup can use any virtual machine that is compatible with the PVM semantics, which allows the Smart Rollup to be more efficient.

Using the PVM and optionally a compatible VM guarantees that if a divergence in results is found, it can be tracked down to a single elementary step that was not executed correctly by some node. In this way, multiple nodes can run the same rollup and each node can verify the state of the rollup.

For a tutorial on Smart Rollups, see Deploy a Smart Rollup.

For reference on Smart Rollups, see Smart Optimistic Rollups in the Octez documentation.

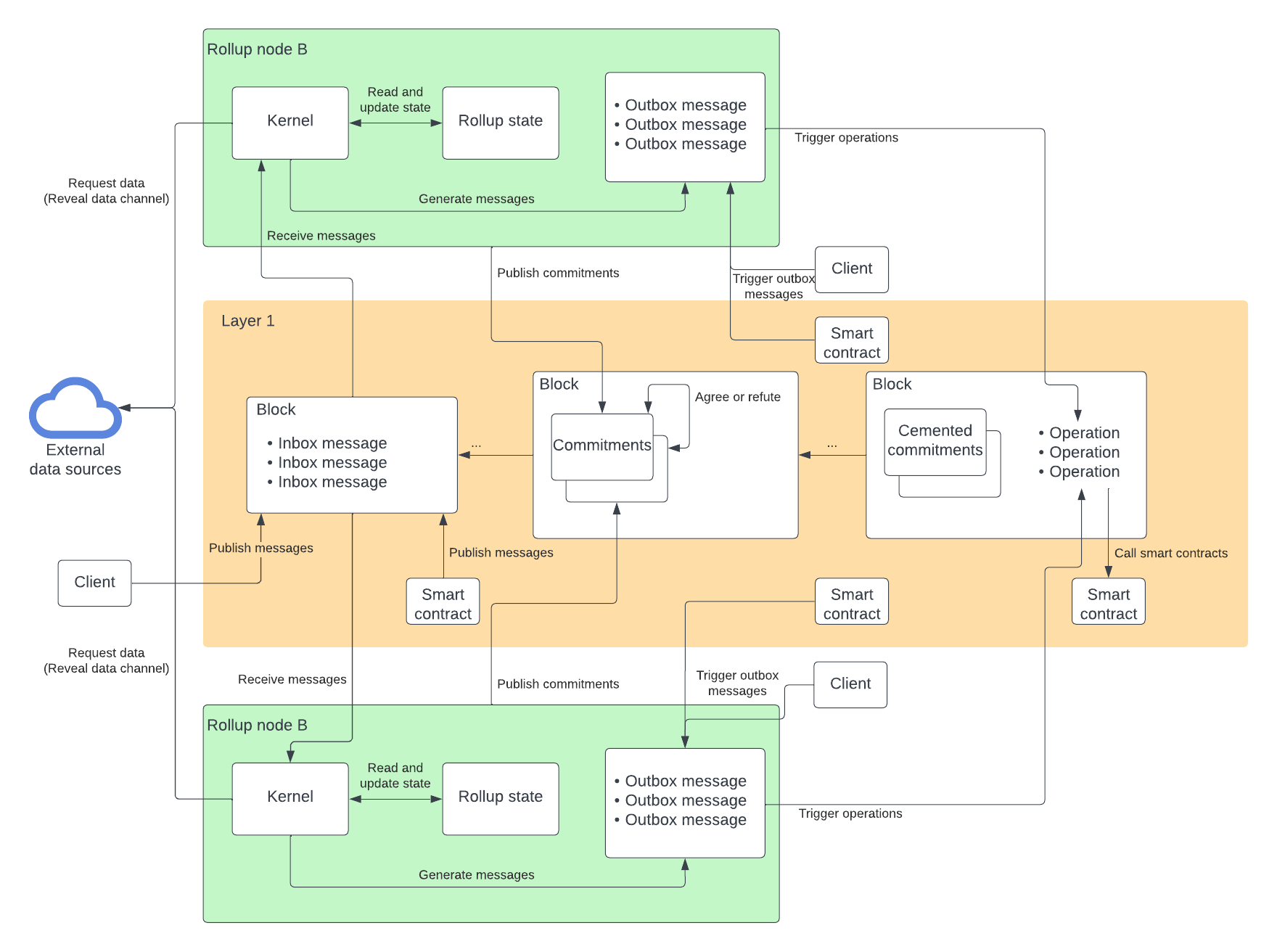

This diagram shows a high-level view of how Smart Rollups interact with layer 1:

Uses for Smart Rollups

-

Smart Rollups allow you to run large amounts of processing and manipulate large amounts of data that would be too slow or expensive to run on layer 1.

-

Smart Rollups can run far more transactions per second than layer 1.

-

Smart Rollups allow you to avoid some transaction fees and storage fees.

-

Smart Rollups can retrieve data from outside the blockchain in specific ways that smart contracts can't.

-

Smart Rollups can implement different execution environments, such as execution environments that are compatible with other blockchains. For example, Smart Rollups enable Etherlink, which makes it possible to run EVM applications (originally written for Ethereum) on Tezos.

Communication

Smart Rollups are limited to information from these sources:

- The Smart Rollup inbox, which contains messages from layer 1 to all rollups

- The reveal data channel, which allows Smart Rollups to request information from outside sources

- The Data Availability Layer

These are the only sources of information that rollups can use. In particular, Smart Rollup nodes cannot communicate directly with each other; they do not have a peer-to-peer communication channel like layer 1 nodes.

Rollup inbox

Each layer 1 block has a rollup inbox that contains messages from layer 1 to all rollups. Anyone can add a message to this inbox and all messages are visible to all rollups. Smart Rollups filter the inbox to the messages that they are interested in and act on them accordingly.

The messages that users add to the rollup inbox are called external messages.

For example, users can add messages to the inbox with the Octez client send smart rollup message command.

Similarly, smart contracts can add messages in a way similar to calling a smart contract entrypoint, by using the Michelson TRANSFER_TOKENS instruction.

The messages that smart contracts add to the inbox are called internal messages.

Each block also contains the following internal messages, which are created by the protocol:

Start of level, which indicates the beginning of the blockInfo per level, which includes the timestamp and block hash of the preceding blockEnd of level, which indicates the end of the block

Smart Rollup nodes can use these internal messages to know when blocks begin and end.

Commitments

Some Smart Rollup nodes post commitments to layer 1, which include a hash of the current state of the kernel. If any node's commitment is different from the others, they play a refutation game to determine the correct commitment, eliminate incorrect commitments, and penalize the nodes that posted incorrect commitments. This process ensures the security of the Smart Rollup by verifying that the nodes are running the kernel faithfully.

Only Smart Rollup nodes running in operator or maintenance mode post these commitments on a regular basis. Nodes running in other modes such as observer mode run the kernel and monitor the state of the Smart Rollup just like nodes in operator or maintenance mode, but they do not post commitments. Nodes running in accuser mode monitor other commitments and post their own commitment only when it differs from other commitments.

Bonds

When a user runs a node that posts commitments, the protocol automatically locks a bond of 10,000 liquid, unstaked tez from user's account as assurance that they are running the kernel faithfully. If the node posts a commitment that is refuted, they lose their bond, as described in Refutation periods.

Because nodes have the length of the refutation to challenge another node's commitment, the bond stays locked until the end of the refutation period for the last commitment that the node posted. After that refutation period ends, the node operator can recover the bond, which unlocks their tez. To simplify the process, node operators can switch to bailout mode, which does not post commitments but continues to defend previously made commitments until the last refutation period ends.

Reveal data channel

Smart Rollups can request arbitrary information through the reveal data channel. Importantly, as opposed to internal and external messages, the information that passes through the reveal data channel does not pass through layer 1, so it is not limited by the bandwidth of layer 1 and can include large amounts of data.

The reveal data channel supports these requests:

-

A rollup node can request an arbitrary data page up to 4KB if it knows the blake2b hash of the page, known as preimage requests. To transfer more than 4KB of data, rollups must use multiple pages, which may contain hashes that point to other pages.

-

A rollup node can request information about the rollup, including the address and origination level of the rollup, known as metadata requests.

Smart Rollup lifecycle

The general flow of a Smart Rollup goes through these phases:

- Origination: A user originates the Smart Rollup to layer 1.

- One or more users start Smart Rollup nodes.

- Commitment periods: The Smart Rollup nodes receive the messages in the Smart Rollup inbox, run processing based on those messages, generate but do not run outbox messages, and publish a hash of their state at the end of the period, called a commitment.

- Refutation periods: Nodes can publish a concurrent commitment to refute a published commitment.

- Triggering outbox messages: When the commitment can no longer be refuted, any client can trigger outbox messages, which create transactions.

Here is more information on each of these phases:

Origination

Like smart contracts, users deploy Smart Rollups to layer 1 in a process called origination.

The origination process stores data about the rollup on layer 1, including:

- An address for the rollup, which starts with

sr1 - The type of proof-generating virtual machine (PVM) for the rollup, which defines the execution engine of the rollup kernel; currently only the

wasm_2_0_0PVM is supported - The installer kernel, which is a WebAssembly program that allows nodes to download and install the complete rollup kernel

- The Michelson data type of the messages it receives from layer 1

- The genesis commitment that forms the basis for commitments that rollups nodes publish in the future

After it is originated, anyone can run a Smart Rollup node based on this information.

Commitment periods

Starting from the rollup origination level, levels are partitioned into commitment periods of 60 consecutive layer 1 blocks. During each commitment period, each rollup node receives the messages in the rollup inbox, processes them, and updates its state.

Because Smart Rollup nodes behave in a deterministic manner, their states should all be the same if they have processed the same inbox messages with the same kernel starting from the same origination level. This state is referred to as the "state of the rollup."

Any time after each commitment period, Smart Rollup nodes in operator mode or maintenance mode publish a hash of their state to layer 1 as part of its commitment. Each commitment builds on the previous commitment, and so on, back to the genesis commitment from when the Smart Rollup was originated. The protocol locks 10,000 tez as a bond from the operator of each node that posts commitments.

At the end of a commitment period, the next commitment period starts.

Refutation periods

Because the PVM is deterministic and all of the inputs are the same for all nodes, any honest node that runs the same Smart Rollup produces the same commitment. As long as nodes publish matching commitments, they continue running normally.

When the first commitment for a past commitment period is published, a refutation period starts, during which any rollup node can publish its own commitment for the same commitment period, especially if it did not achieve the same state. During the refutation period for a commitment period, if two or more nodes publish different commitments, two of them play a refutation game to identify the correct commitment. The nodes automatically play the refutation game by stepping through their logic using the PVM to identify the point at which they differ. At this point, the PVM is used to identify the correct commitment, if any.

Each refutation game has one of two results:

-

Neither commitment is correct. In this case, the protocol burns both commitments' stakes and eliminates both commitments.

-

One commitment is correct and the other is not. In this case, the protocol eliminates the incorrect commitment, burns half of the incorrect commitment's stake, and gives the other half to the correct commitment's stake.

This refutation game happens as many times as is necessary to eliminate incorrect commitments. Because the node that ran the PVM correctly is guaranteed to win the refutation game, a single honest node is enough to ensure that the Smart Rollup is running correctly. This kind of Smart Rollup is called a Smart Optimistic Rollup because the commitments are assumed to be correct until they are proven wrong by an honest rollup node.

When there is only one commitment left, either because all nodes published identical commitments during the whole refutation period or because this commitment won the refutation games and eliminated all other commitments, then this correct commitment can be cemented by a dedicated layer 1 operation and becomes final and unchangeable. The commitments for the next commitment period build on the last cemented commitment.

The refutation period lasts for a set number of blocks based on the smart_rollup_challenge_window_in_blocks protocol constant.

This period adds up to two weeks on Mainnet and Ghostnet, but it could be different on other networks.

However, the refutation period for a specific commitment can vary if it is uncemented when a protocol upgrade changes the block times.

When the time between blocks changes, the protocol adjusts the number of blocks in the refutation period to keep the refutation period at the same real-world length. It uses this new number of blocks to determine whether commitments can be cemented.

For this reason, if the block time gets shorter during the commitment's refutation period, the number of blocks that must pass before cementing a commitment increases. Therefore, commitments that are not cemented when the number of blocks changes must wait slightly longer before they can be cemented.

This variation affects only commitments that are not cemented when the layer 1 protocol upgrade happens. The delay is based on how much the block times changed and on how close a commitment is to being cemented when the number of blocks in the refutation period changes.

The maximum change is the new block time divided by the old block time multiplied by the standard refutation period. For example, if the new block time is 8 seconds and the old block time is 10 seconds, the maximum addition to a commitment's refutation period is 10 / 8, or 1.25 times the standard 14-day period. Commitments that are close to being cemented when the block time changes have the largest change to their refutation periods, while commitments that are made close to when the block time changes have a very small change.

Triggering outbox messages

Smart Rollups can generate transactions to run on layer 1, but those transactions do not run immediately. When a commitment includes layer 1 transactions, these transactions go into the Smart Rollup outbox and wait for the commitment to be cemented.

After the commitment is cemented, clients can trigger transactions in the outbox with the Octez client execute outbox message command.

When they trigger a transaction, it runs like any other call to a smart contract.

For more information, see Triggering the execution of an outbox message in the Octez documentation.

Bailout process

Nodes that do not post commitments can stop running at any time without risk because they do not have a bond. Nodes that post commitments cannot stop immediately without risking their bonds because they will not be online to participate in the refutation game.

For this reason, nodes can switch to bailout mode to prepare to shut down without risking their bonds. In bailout mode, nodes defend their existing commitments without posting new commitments. When their final commitment is cemented, they can shut down safely. For more information about node modes, see Smart rollup node in the Octez documentation.

Examples

For examples of Smart Rollups, see this repository: https://gitlab.com/tezos/kernel-gallery.